Join Us On Social Media!

Media Gallery

📝 Southport Model Boat Club Open Day 270725

5 months ago by 🇬🇧 SouthportPat ( Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)✧ 88 Views · 5 Likes

Flag

💬 Add Comment

Sailings at Southport Model Boat Club Open Day 270725

▲

⟩⟩

Wolle

Len1

hermank

Ray

Nickthesteam

Login To

Remove Ads

Remove Ads

📝 SOUTHPORT MODEL BOAT CLUB

5 months ago by 🇬🇧 EricM ( Recruit)

Recruit)

Recruit)

Recruit)✧ 102 Views · 5 Likes · 2 Comments

Flag

💬 Add Comment

Please note that our website address is no longer functioning. We are in the process of rebuilding with a new address. Apologies for any inconvenience caused. Relaunch will be announced. Eric Morris. Club Secretary.

▲

⟩⟩

Nickthesteam

Len1

SouthportPat

hermank

DWBrinkman

|

💬 Re: SOUTHPORT MODEL BOAT CLUB

5 months ago by 🇬🇧 sparky (

Recruit) Recruit)✧ 55 Views · 1 Like

Flag

Please stop sending emails on a daily basis to Victor Robinson. I find them very upsetting as he passed away 15 months ago. Thank you.

▲

⟩⟩

hermank

|

|

💬 Re: SOUTHPORT MODEL BOAT CLUB

5 months ago by 🇬🇧 zooma (

Vice Admiral) Vice Admiral)✧ 97 Views · 4 Likes

Flag

Thanks for letting us know Eric, I hope you are able to get the new site up and running shortly.

Bob (zooma). No idea why I am known as “zooma too” when using my iPhone. Very annoying and unable to correct. ▲

⟩⟩

hermank

zooma

Len1

SouthportPat

|

📝 "Sailor Sam"

5 months ago by 🇬🇧 philcaretaker ( Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)✧ 111 Views · 16 Likes · 1 Comment

Flag

💬 Add Comment

Hi, I`m Sailor Sam - I`m rough but ready - and here just for fun at the Buxton Model Boat Club.

Along with Bill & Ben, Kayak Kate and Dinghy Dan we hope to bring Fun, Entertainment and inspiration to young and old RC Model enthusiasts.

Along with Bill & Ben, Kayak Kate and Dinghy Dan we hope to bring Fun, Entertainment and inspiration to young and old RC Model enthusiasts.

▲

⟩⟩

Nickthesteam

Ray

GavJ

Rookysailor

Len1

xtramaths

hermank

Wolle

DWBrinkman

peterd

EdW

DuncanP

algon

jumpugly

GaryLC

SimpleSailor

|

💬 Re: "Sailor Sam"

5 months ago by 🇬🇧 DuncanP (

Commander) Commander)✧ 112 Views · 3 Likes

Flag

Amazing animated sailors! The chap smoking made me laugh. Well done everyone - superb

▲

⟩⟩

Len1

hermank

DWBrinkman

|

📝 Boats in the park Hamilton steam museum

6 months ago by 🇨🇦 GARTH ( Captain)

Captain)

Captain)

Captain)✧ 122 Views · 11 Likes · 1 Comment

Flag

💬 Add Comment

Back in May, we put on a show at the Hamilton Steam Museum. I forgot that I had recorded the Balloon Buster, so here's that video. It sure was cold in May, and the Pool leaked like a sieve due to all the holes those boats put in the liner.

▲

⟩⟩

EdW

algon

RNinMunich

SimpleSailor

Ray

hermank

RossM

peterd

Ronald

RodC

Len1

|

💬 Re: Boats in the park Hamilton steam museum

6 months ago by 🇨🇦 Ronald (

Fleet Admiral) Fleet Admiral)✧ 115 Views · 2 Likes

Flag

Thanks for sharing Garth. A couple of those balloons must have had thick skins or your Lances were dull.

▲

⟩⟩

Len1

hermank

|

📝 Latest Sailings at SMBC #3

6 months ago by 🇬🇧 SouthportPat ( Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)✧ 125 Views · 8 Likes · 1 Comment

Flag

💬 Add Comment

See the latest projects sailing at SMBC

▲

⟩⟩

GavJ

algon

SimpleSailor

hermank

peterd

Len1

Ray

EdW

|

💬 Re: Latest Sailings at SMBC #3

5 months ago by 🇬🇧 zooma (

Vice Admiral) Vice Admiral)✧ 93 Views · 2 Likes

Flag

Nice to see anything on here from SMBC.

Bob(zooma) No idea why I am called “zooma too” when using my iPhone. Very annoying annoying but unable to correct it. ▲

⟩⟩

zooma

Len1

|

📝 Latest Sailings at SMBS #2

6 months ago by 🇬🇧 SouthportPat ( Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)✧ 125 Views · 4 Likes

Flag

💬 Add Comment

See the latest projects sailing at SMBC

▲

⟩⟩

hermank

Len1

jumpugly

EdW

📝 Latest Sailings at SMBC #1

6 months ago by 🇬🇧 SouthportPat ( Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)✧ 125 Views · 7 Likes

Flag

💬 Add Comment

See the latest projects sailing at SMBC

▲

⟩⟩

algon

hermank

Len1

Ray

EdW

Nickthesteam

AlessandroSPQR

📝 My grandfathers ship USS Canopus AS-9 Submarine tender.

6 months ago by 🇺🇸 thadlietz ( Chief Petty Officer 2nd Class)

Chief Petty Officer 2nd Class)

Chief Petty Officer 2nd Class)

Chief Petty Officer 2nd Class)✧ 126 Views · 6 Likes

Flag

💬 Add Comment

A long read but the pdf is the story of the USS Canopus and it's last stand at Corregidor. He was captured at the fall and survived the Bataan death march and after some time was shipped to Japan to work in a copper mine until liberation. He died in 1977 after retiring as a senior member of IBM.

▲

⟩⟩

AlessandroSPQR

LeeA

Nickthesteam

Len1

EdW

hermank

📝 Newish member

6 months ago by 🇬🇧 mjbb1951 ( Able Seaman)

Able Seaman)

Able Seaman)

Able Seaman)✧ 139 Views · 15 Likes · 3 Comments

Flag

💬 Add Comment

▲

⟩⟩

algon

SimpleSailor

EdW

IanL1

RodC

Len1

jumpugly

DWBrinkman

PhilH

Stuart Mackay

Ray

roycv

AlessandroSPQR

hermank

peterd

|

💬 Re: Newish member

6 months ago by 🇦🇺 peterd (

Sub-Lieutenant) Sub-Lieutenant)✧ 141 Views · 3 Likes

Flag

We sail several in our group, I have two one of which is raced every Sunday. At one stage we would have up to 15 racing weekly. They are a great introduction to rc sailing.

▲

⟩⟩

AlessandroSPQR

Len1

hermank

|

|

Login To

Remove Ads 💬 Re: Newish member

6 months ago by 🇬🇧 mjbb1951 (

Able Seaman) Able Seaman)✧ 137 Views · 3 Likes

Flag

yes it is a Wee Nip

▲

⟩⟩

Len1

peterd

hermank

|

|

💬 Re: Newish member

6 months ago by 🇦🇺 peterd (

Sub-Lieutenant) Sub-Lieutenant)✧ 144 Views · 3 Likes

Flag

Is that a WeeNip sailboat?

▲

⟩⟩

Len1

AlessandroSPQR

hermank

|

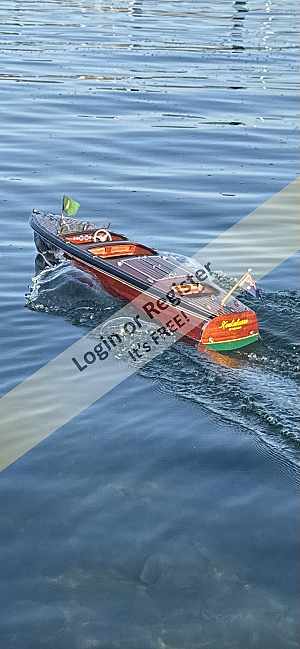

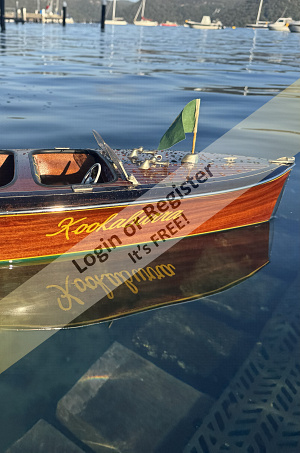

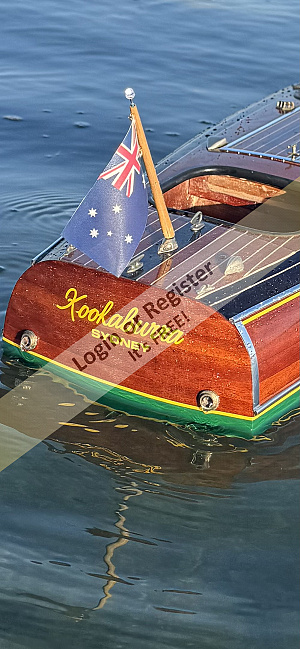

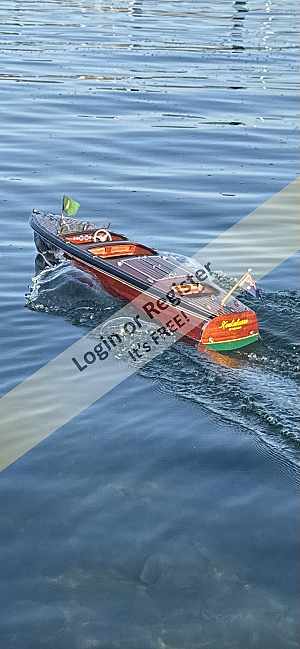

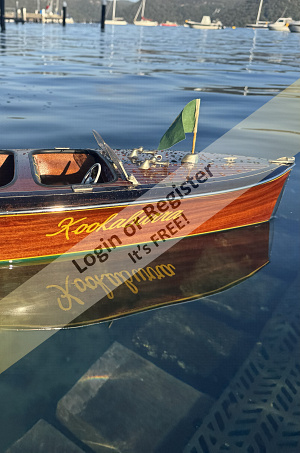

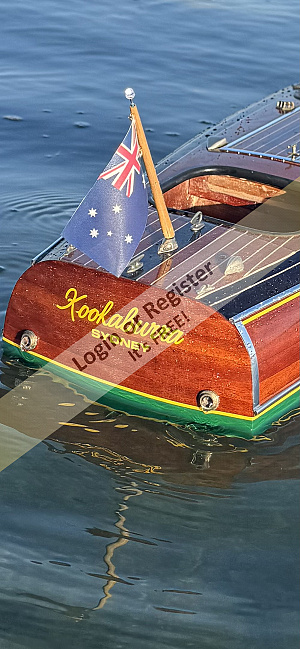

📝 1938 Chris craft barrel back

6 months ago by 🇦🇺 Schmango ( Petty Officer 1st Class)

Petty Officer 1st Class)

Petty Officer 1st Class)

Petty Officer 1st Class)✧ 153 Views · 19 Likes · 4 Comments

Flag

💬 Add Comment

Built this in the late 90s and never really had the skills at the time to make the finish the high quality these boats deserve. After sitting on the shelf for over 25 years I finally dusted it off and stripped it back to bare timber. I nervously applied a thin west system epoxy to it and spent what felt like an eternity sanding it up to 800 grit then polishing it . It’s a beautiful boat now and resembles the boats that were used for joy rides in Sydney harbour . I used cali graphics for the decals and they are awesome . Also added led lights . Enjoy

▲

⟩⟩

SouthportPat

Kevin-56

MartyV

ColinJ2

RodC

Ray

ZdenekB

EdW

DuncanP

RNinMunich

jumpugly

IanL1

Ronald

BarryS

Len1

hermank

peterd

ARL58

Mike Stoney

|

💬 Re: 1938 Chris craft barrel back

5 months ago by 🇬🇧 EricM (

Recruit) Recruit)✧ 101 Views · 1 Like

Flag

I have the same model. Wish it looked half as good as yours. Cogratulations.👍

▲

⟩⟩

Len1

|

|

Login To

Remove Ads 💬 Re: 1938 Chris craft barrel back

6 months ago by 🇳🇿 IanL1 (

Midshipman) Midshipman)✧ 151 Views · 4 Likes

Flag

Just beautiful, well done. I notice you are flying small flags, where did you source them from as I am looking for a small Italian flag to suit my Venice water taxi.👍👍

▲

⟩⟩

Len1

hermank

jumpugly

peterd

|

|

💬 Re: 1938 Chris craft barrel back

6 months ago by 🇨🇦 Ronald (

Fleet Admiral) Fleet Admiral)✧ 152 Views · 4 Likes

Flag

Beautifully finished and worth the effort you spent to get it done.

▲

⟩⟩

Len1

jumpugly

peterd

hermank

|

|

💬 Re: 1938 Chris craft barrel back

6 months ago by 🇦🇺 peterd (

Sub-Lieutenant) Sub-Lieutenant)✧ 157 Views · 4 Likes

Flag

Beautiful job and worth the wait.

▲

⟩⟩

jumpugly

Len1

hermank

Schmango

|

📝 Graupner Optimist

6 months ago by 🇨🇦 GARTH ( Captain)

Captain)

Captain)

Captain)✧ 172 Views · 15 Likes · 6 Comments

Flag

💬 Add Comment

Today, Optimist saw real water. I had a mini-soling also, but another member had an 88 transmitted, & my mini-soling is also on 88, so it took me a while to get the courage to put the Optimist So today was for sail boats but you usually have a member that wants to test out his speed boat that's has a great paint job . He picked up a seagull feather that really slowed him down.

▲

⟩⟩

RodC

RNinMunich

Ray

B rian J ames

IanL1

Len1

AlessandroSPQR

Mike Stoney

Trident73

DuncanP

EdW

hermank

peterd

jumpugly

Ronald

|

💬 Re: Graupner Optimist

6 months ago by 🇩🇪 RNinMunich (

Fleet Admiral) Fleet Admiral)✧ 153 Views · 4 Likes

Flag

BJ. 👎👎👎

Be happy that I am no longer a Moderator! To quote your own words: "I (i.e. you) must get a 'life'," I believe that you need some help, but unfortunately not the kind of help that you can receive here on a Model Boats enthusiast site. Doug ▲

⟩⟩

Len1

Mike Stoney

B rian J ames

hermank

|

|

Login To

Remove Ads 💬 Re: Graupner Optimist

6 months ago by 🇦🇺 B rian J ames (

Petty Officer 2nd Class) Petty Officer 2nd Class)✧ 152 Views · 2 Likes

Flag

Pat, Isn't using the WWW, (slightly) cheating? I.E. I haven't a 'clue'! But 'Glue', I do know a 'little' about, sticky stuff. If 'Sikaflex' sticks to fingers, it must be pretty good? But seriously folks, 'preparation, preparation, preparation', that & spread the contact area, & reinforce with 'glass, (tape). 'B J'. 🤔 Keep on Modelling!

▲

⟩⟩

Len1

hermank

|

|

💬 Re: Graupner Optimist

6 months ago by 🇦🇺 B rian J ames (

Petty Officer 2nd Class) Petty Officer 2nd Class)✧ 156 Views · 2 Likes

Flag

Sorry, Graupner, Too busy being a 'Smartass', to add the Soling also, (as well as the Optimist), looks fantastic. Great work, keep it up, (no rude comment included, for a change). 'B J'.

▲

⟩⟩

Len1

hermank

|

|

💬 Re: Graupner Optimist

6 months ago by 🇧🇪 hermank (

Rear Admiral) Rear Admiral)✧ 168 Views · 3 Likes

Flag

Michel C

You are a very wise and thoughtfull sailor!👍👍 ▲

⟩⟩

Len1

Mike Stoney

AlessandroSPQR

|

|

💬 Re: Graupner Optimist

6 months ago by 🇨🇭 Mike Stoney (

Rear Admiral) Rear Admiral)✧ 163 Views · 3 Likes

Flag

Hello Garth!

You've made a real effort, I like it! For me, the renovation of the optimist is still to come, as I'm retired . . . What else I would personally recommend . . I hope I'm not standing on the feet of our sailing specialists . . is a small water pump. Suck in at the front and expel at the back. This is my experience, which brought the boat back to me when the wind failed completely. Just a tip from experience . . Tinkerer Michel-C. ▲

⟩⟩

Len1

AlessandroSPQR

hermank

|

|

💬 Re: Graupner Optimist

6 months ago by 🇦🇺 B rian J ames (

Petty Officer 2nd Class) Petty Officer 2nd Class)✧ 163 Views · 3 Likes

Flag

And a great day was had by all! Except the seagull? Well done you! Trivia! I heard that some 'Optimist Class' sailor, put 'lifting hydrofoils' on an 8' Opt. that actually worked! Imagine! An 8' dink with a kid 'pilot'?, Flying off the water! WOW! 'B J'.

▲

⟩⟩

Len1

Mike Stoney

hermank

|

Login To

Remove Ads

Remove Ads

📝 Just for fun !

6 months ago by 🇬🇧 philcaretaker ( Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)✧ 168 Views · 9 Likes · 1 Comment

Flag

💬 Add Comment

Nice calm day to "chuck" a sail on the front of my camera boat to maintain downwind speed when not using noisy power !!.

Due to weedy conditions , didn`t bother about no keel - Shall not do that again - AGH !!!

All equipment , RX, battery, motor ,esc and camera dried out, tested and OK.

Phew ! - that was lucky.

Just for fun !.

Due to weedy conditions , didn`t bother about no keel - Shall not do that again - AGH !!!

All equipment , RX, battery, motor ,esc and camera dried out, tested and OK.

Phew ! - that was lucky.

Just for fun !.

▲

⟩⟩

MartyV

Len1

Mike Stoney

peterd

jumpugly

StuS1

hermank

SimpleSailor

EdW

|

💬 Re: Just for fun !

6 months ago by 🇬🇧 muddy (

Sub-Lieutenant) Sub-Lieutenant)✧ 166 Views · 1 Like

Flag

Ohh dear.. Pleased you managed to rescue all the gear though Phil.. My apologies for the nosiness of this question, but what was the other boat involved, the green and white one ? the motor sailer, or thats what it looked like to me.. Thanks for the post.. ATB Muddy..

▲

⟩⟩

hermank

|

📝 USS Melvin

7 months ago by 🇨🇦 GARTH ( Captain)

Captain)

Captain)

Captain)✧ 177 Views · 9 Likes · 2 Comments

Flag

💬 Add Comment

My old Lindberg model of the USS Melvin DD 680 has sunk at least twice in the model boat pond at Spencers, so I've decided to add about 1/2 inch to the bottom of the hull. It's an experiment. I think if the hull is a little bigger, the wind won't tip it over. I also upgraded the motor & rudder servo. Hope my experiment works.P/S seemed to work in the tub. I need to get it working properly as CMM Modelers is having a Warship Regatta at Spencer's Sunday,Sept 14th at 9 AM till noon

▲

⟩⟩

Mike Stoney

EdW

IanL1

jumpugly

hermank

Wolle

Fred

Ronald

RodC

|

💬 Re: USS Melvin

6 months ago by 🇨🇦 RodC (

Lieutenant Commander) Lieutenant Commander)✧ 167 Views · 3 Likes

Flag

Garth, at least at SPENCERS its unlikely to become a total loss in 5" of water. A very safe venue in that respect.

▲

⟩⟩

hermank

AlessandroSPQR

GARTH

|

|

💬 Re: USS Melvin

7 months ago by 🇨🇦 Ronald (

Fleet Admiral) Fleet Admiral)✧ 175 Views · 1 Like

Flag

Hope to see you and other Confederation members at the Nathan Phillips Square event tomorrow 10-3.

▲

⟩⟩

hermank

|

📝 Pats HMS Manchester Video VE Day Celebrations 04 May 2025

7 months ago by 🇬🇧 SouthportPat ( Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)✧ 201 Views · 13 Likes · 2 Comments

Flag

💬 Add Comment

HMS Manchester was a Town-class light cruiser built for the Royal Navy in the late 1930s, one of three ships in the Gloucester subclass. Completed in 1938, she was initially deployed with the East Indies Station and had a relatively short but active career. When World War II began in September 1939, the cruiser began escorting convoys in the Indian Ocean until she was ordered home two months later. In late December Manchester began conducting patrols in the Norwegian Sea enforcing the blockade of Germany. Beginning in April 1940 the ship played a minor role in the Norwegian Campaign, mostly escorting convoys. She was assigned to anti-invasion duties in May–November in between refits.

In November the cruiser was tasked to escort a convoy through the Mediterranean and participated in the Battle of Cape Spartivento. Manchester was refitting during most of early 1941, but began patrolling the southern reaches of the Arctic Ocean in May. The cruiser was detached to escort a convoy to Malta in July and she was badly damaged by an aerial torpedo en route. Repairs were not completed until April 1942 and the ship spent the next several months working up and escorting convoys.

Manchester participated in Operation Pedestal, another Malta convoy, in mid-1942; she was torpedoed by two Italian motor torpedo boats and subsequently scuttled by her crew. Casualties were limited to 10 men killed by the torpedo and 1 who drowned as the crew abandoned ship.[Note 1] Most of the crew were interned by the Vichy French when they drifted ashore. After their return in November, the ship's leadership was court martialled; the captain and four other officers were convicted for prematurely scuttling their ship.

Design and description

The Town-class light cruisers were designed as counters to the Japanese Mogami-class cruisers built during the early 1930s and the last batch of three ships was enlarged to accommodate more fire-control equipment and thicker armour.[2] The Gloucester group of ships were a little larger than the earlier ships of the class and received additional armour.[3] They displaced 9,400 long tons (9,551 t) at standard load and 11,650 long tons (11,837 t) at deep load. The cruisers had an overall length of 591 feet 6 inches (180.3 m), a beam of 62 feet 4 inches (19 m) and a draught of 20 feet 7 inches (6.3 m).[4] They were powered by four Parsons geared steam turbine sets, each driving one shaft using steam provided by four Admiralty 3-drum boilers. The turbines developed a total of 82,500 shaft horsepower (61,500 kW) and were designed to give a maximum speed of 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph).[5] During her sea trials on 28 March – 7 April 1938, Manchester achieved an average speed of 32.6 knots (60.4 km/h; 37.5 mph) from 84,461 shp (62,983 kW).[6] The ships carried enough fuel oil to give them a range of 6,000 nautical miles (11,000 km; 6,900 mi) at 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph). The ship's complement was 800–815 officers and ratings.[5]

The Town-class ships mounted twelve BL six-inch (152 mm) Mk XXIII guns in four triple-gun turrets, one superfiring pair each fore and aft of the superstructure. The turrets were designated 'A', 'B', 'X' and 'Y' from front to rear. Their secondary armament consisted of eight QF four-inch (102 mm) Mk XVI dual-purpose guns in twin mounts. Their light anti-aircraft armament consisted of a pair of quadruple mounts for the two-pounder (40-millimetre (1.6 in)) ("pom-pom") anti-aircraft (AA) guns and two quadruple mounts for 0.5-inch (12.7 mm) Vickers AA machine guns. The ships carried two above-water, triple mounts for 21-inch (533 mm) torpedoes.[7] The Towns lacked a full-length waterline armour belt, although the sides of the Gloucester group's boiler and engine rooms and the sides of the magazines were protected by 4.5 inches (114 mm) of armour.[7] The top of the magazines and the machinery spaces were protected by 1.25–2 inches (32–51 mm) of armour. The armour plates on the main-gun turrets had a thickness of 2–4 inches.[3]

The cruisers were designed to handle three Supermarine Walrus amphibious reconnaissance aircraft, one on the fixed D1H catapult and the others in the two hangars abreast the forward funnel, but only two were ever carried in service. A pair of 15,000-pound (6,800 kg) cranes were fitted to handle the aircraft and the ships' boats.[8]

Modifications

When Manchester returned home in November 1939, she was refitted with degaussing equipment and probably had her aft high-angle director-control tower (DCT) fitted. During a brief refit in November 1940, the ship was probably equipped with a Type 286 search radar. During a longer refit in January–March 1941, Manchester's hull was reinforced and her Vickers machine guns were exchanged for an ex-Army 40-millimeter Bofors AA gun atop 'B' turret and five 20-millimetre (0.8 in) Oerlikon AA guns. A Type 284 gunnery radar was installed on the roof of the main armament DCT atop the bridge during this refit. Additional splinter plating to protect the secondary armament and torpedo tubes was probably added at this time, as was an ASDIC sonar system.[9]

Two additional ex-Army Bofors guns reinforced the ship's anti-aircraft suite before she participated in Operation Substance in June 1941. Manchester was torpedoed during this convoy escort mission and while she was being repaired in the United States and Britain, she received three more Oerlikon guns for a total of eight weapons, six of which were positioned in the superstructure, one on the roof of 'X' turret and one on the quarterdeck. Two more ex-Army Bofors guns were added amidships before the ship participated in Operation Pedestal in August 1942. When the repairs were completed in April 1942, her radar suite consisted of a Type 279 early-warning radar, the Type 284 system for her main armament, two Type 285 gunnery radars for the four-inch guns, a Type 273 surface-search radar to replace the Type 286 and probably a pair of Type 282 gunnery radars for the "pom-pom" directors.[10]

Construction and career

Manchester, the first ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy,[11] was ordered on 23 October 1935 from Hawthorn Leslie and Company. The ship was laid down at their Hebburn shipyard on 28 March 1936 and was launched on 12 April 1937 by the wife of Joseph Toole, the Lord Mayor of Manchester. She was commissioned on 4 August 1938 and departed for her first duty assignment with the 4th Cruiser Squadron in the East Indies on 24 September.[12]

After arriving in the British Colony of Aden, Yemen, on 12 October, Manchester was met by the heavy cruiser Norfolk, the station flagship, and the two ships proceeded to Bombay, British India, and then to Trincomalee, British Ceylon by the end of the month where they spent the next month working up. They spent the next month making port visits on the western coast of British India before returning to Ceylon for a maintenance period in Colombo's dockyard. Ports along the Bay of Bengal were visited in February–March 1939, before the two cruisers arrived in Singapore in the British Straits Settlements on 13 March. They conducted exercises with the aircraft carrier Eagle, the heavy cruiser Kent and the submarine depot ship Medway off the eastern coast of Malaya for the next several weeks.[13]

Visiting Port Blair in the Andaman Islands en route on 28 March, Manchester arrived at Trincomalee to prepare for a refit in Colombo. Rising tensions in Europe caused the refit to be delayed for a week and her refit was completed in early June. She began a tour of Indian Ocean ports on 6 June, supporting an aeronautical survey in Diego Garcia three days later with fuel and supplies before arriving in the British Protectorate of Zanzibar on 20 June. The ship began moving up the African coast until she rendezvoused with her sister ship Gloucester, the new station flagship, at Kilindini Harbour in British Kenya on 14 July. The sisters sailed to Aden when they met the sloops Egret and Fleetwood later that month to practice convoy escort tactics in light of the potential threat posed by Italian colonies on the Red Sea.[14]

Early war service

Manchester had just returned from a patrol in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden when Britain declared war on Nazi Germany on 3 September 1939. Together with Gloucester, she sailed for Colombo after refuelling. On 25 September, the ship rendezvoused with the sloop Rochester to help escort an Indian troop convoy through the Red Sea. Manchester escorted an Anglo-French convoy there before rendezvousing with the ocean liner RMS Empress of Australia in the Gulf of Suez to escort her to Colombo. The cruiser was ordered home on 10 November and arrived at Malta eight days later, where Vice-Admiral Geoffrey Layton hoisted his flag as commander of the 18th Cruiser Squadron (CS). The ship arrived in HM Dockyard, Portsmouth on the 25th and was docked to have storm damage and some other defects repaired.[15]

Her refit was completed on 22 December and she joined the Home Fleet at Scapa Flow two days later. Later that month, Manchester was attached to the Northern Patrol, where she was tasked to enforce the blockade of Germany, searching for German blockade runners and contraband material. On 21 February 1940 the ship helped to capture the 4,709-gross register ton (GRT) German merchantman Wahehe.[16] She remained on this duty until early April, although the cruiser was in Scapa Flow when it was attacked by German aircraft on 16 March. Manchester's gunners were unprepared for the attack and her shells were ineffectual.[17]

Norwegian campaign

Main article: Norwegian campaign

The 18th CS was relieved of its attachment to the Northern Patrol and was assigned to escort convoys to and from Norway. On 7 April Manchester, her half-sister Southampton, the anti-aircraft cruiser Calcutta and four destroyers were escorting the 43 ships of Convoy ON-25 bound for Norway. After the Royal Air Force (RAF) reported German ships in the North Sea, the convoy was ordered to turn back and the two light cruisers were to rendezvous with the Home Fleet in the Norwegian Sea. Their orders were later modified to patrol the southern part of the sea. Late on the 8th, the Admiralty ordered the ships to rendezvous with the Home Fleet lest they be caught between the two groups of German ships believed to be at sea; this was accomplished early on the morning of 9 April.[18]

Reinforced by their sisters Sheffield and Glasgow and seven destroyers of the 4th Destroyer Flotilla, the 18th CS was ordered to attack the Königsberg-class cruiser believed to be in Bergen, Norway, later that morning. That afternoon the RAF reported two cruisers in Bergen and the Admiralty cancelled the operation. The Luftwaffe had been tracking the squadron as it approached Bergen and bombers from KG 26 and KG 30 began attacking shortly afterwards. They sank the destroyer Gurkha and near misses damaged Southampton and Glasgow. That night Manchester, Southampton and the 6th Destroyer Flotilla patrolled off Fedjeosen to observe German forces in Bergen and prevent any resupply. The only incident that night was when Manchester spotted a submarine crossing between the two cruisers on the surface; the ship attempted to ram, but only managed a glancing blow. The next morning, the ships were recalled and the cruisers arrived in Scapa Flow that evening to refuel and replenish ammunition.[19]

On 12 April, Captain Herbert Packer assumed command and the ship departed Scapa to rendezvous with the escort for Convoy NP-1 which was loaded with two infantry brigades bound for Narvik, Norway. Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided to take advantage of the unopposed occupation of Namsos on the 14th and ordered that the 146th Infantry Brigade should arrive offshore at dusk on the 15th to reinforce the initial landing force. Layton chose to escort the troopships Empress of Australia and MS Chrobry with Manchester, her half-sister HMS Birmingham (C19), the anti-aircraft cruiser Cairo and three destroyers. The threat of air attack and poor port facilities at Namsos caused the Admiralty to change the destination, but the troops and most of their equipment completed unloading on the 19th. That day the Admiralty ordered most of the ships off Norway home to prepare for further operations so the cruiser headed for Rosyth, Scotland.[20]

Later that day, Manchester was ordered back to the Namsos area to escort Convoy FP-1 back to Britain. On 22 April she returned to Rosyth to begin loading about half of the 15th Infantry Brigade, together with Birmingham and the heavy cruiser York, to be ferried to Åndalsnes and Molde. Manchester disembarked her passengers at the latter town on the 25th and then joined Birmingham to cover three destroyers laying mines near Trondheim. The sisters returned to Scapa Flow on 28 April to refuel. Three days later they arrived at Åndalsnes to evacuate the remaining troops still ashore. Manchester was slightly damaged by splinters from near misses made by the Luftwaffe that were otherwise ineffectual.[21]

On 10 May Manchester and Sheffield were ordered to sea to protect the crippled destroyer Kelly which was being towed home after having been torpedoed by an E-boat. The cruisers engaged Luftwaffe aircraft when they unsuccessfully attacked the next day and then were ordered to return to Rosyth in light of the submarine threat where she began a brief refit. On 26 May, the 18th CS, consisting of Manchester, Birmingham and Sheffield, was transferred to the Humber for anti-invasion duties. They returned to Rosyth on 10 June after the vulnerabilities of Immingham were realised. Layton was relieved by Vice-Admiral Frederick Edward-Collins on 15 June and the ships returned to Immingham on 1 July. Edward-Collins transferred his flag to Birmingham on 4 July after which Manchester sailed to Portsmouth to begin a brief refit. She arrived back in Scapa Flow on 22 August and Edward-Collins immediately returned his flag to the ship. Her stay there was brief as the squadron immediately sailed for Rosyth to resume anti-invasion duties. The squadron returned to Immingham on 3 September as fears of invasion rose. Edward-Collins was relieved by Vice-Admiral Lancelot Holland on 12 November.[22]

On 15 November the ship departed Scapa Flow to rendezvous with a convoy that conveying RAF personnel and equipment to Alexandria, Egypt. After their arrival in Gibraltar on 21 November, Manchester and Southampton loaded roughly 1,400 men and many tons of supplies and departed on the 25th, escorted by Force H. They were to be met by ships of the Mediterranean Fleet south of Sardinia, Italy, the whole affair codenamed Operation Collar. The Italians spotted the convoy and attempted to intercept it on 27 November in the Battle of Cape Spartivento. The British concentrated their cruisers, even though the efficiency of Manchester and Southampton was reduced by their passengers, and engaged their Italian counterparts at long range with little effect. The Italians attempted to disengage, but the British pursued until they risked leaving the convoy unprotected. The subsequent aerial attacks by the Regia Aeronautica (Royal Italian Airforce) failed to damage any British ships. During the battle, Manchester fired 912 shells from her main guns without making a single hit. But she was hit by the Italian battleship Vittorio Veneto causing splinter damage.[23] The ship arrived at Alexandria without further incident on 30 November. She passed through the Mediterranean at high speed without being spotted and arrived at Scapa Flow on 13 December. Holland transferred his flag to her half-sister Edinburgh on 8 January 1941. The cruiser began a lengthy refit at Jarrow on 11 January that lasted until 17 April.[24]

1941

Manchester rejoined the 18th CS at Scapa Flow the following day and spent the rest of the month working up. On 18 May the cruiser and Birmingham were ordered to patrol the Iceland-Faroe Islands gap, but they played no part in the search for the Bismarck as they were repositioned north of Iceland in case the German ships attempted to return to Germany through the Denmark Strait after the battlecruiser Hood was sunk on 24 May. The ships returned to Scapa Flow on 3 June and Packer was relieved by Captain Harold Drew. Manchester sailed on 9 June to Hvalfjord, Iceland, to patrol the Denmark Strait for the rest of the month, returning to Scapa on 3 July.[25]

The ship joined the escort force for Convoy WS-9C bound for Gibraltar on 12 July and arrived there eight days later where she loaded troops and supplies from the convoy to be conveyed to Malta in Operation Substance. The convoy came together on 23 July and the Italians determined that it was bound for Malta. The ships of the Regia Marina (Royal Italian Navy) were not prepared to attack so that was left to the bombers of the Regia Aeronautica. During the first attack that morning Manchester was hit by an Italian aerial torpedo that struck abreast 'X' turret. It blew a 60-foot-long (18.3 m) hole in the hull, disabled both portside propeller shafts, and allowed heavy flooding that caused a 12.5-degree list. The estimated 2,000 long tons (2,032 t) of water also caused the ship to trim down at the stern by 7 feet 6 inches (2.3 m) and filled the aft engine room which meant that only a single propeller shaft was operable. The detonation killed 3 officers and 23 ratings from Manchester's crew and 5 officers and 7 other ranks from the embarked troops. The list was corrected less than three hours after the attack and the cruiser was ordered to return to Gibraltar, escorted by a destroyer. The two ships were unsuccessfully attacked by more Italian bombers later that day and reached their destination on the 26th.[26]

Temporary repairs took until 15 September when the ship then sailed for the Philadelphia Navy Yard in the United States for permanent repairs. This was finished on 27 February 1942, after which she returned to Portsmouth, where final work was completed by the end of April. On her return to service she rejoined the Home Fleet at Scapa Flow on 4 May, spending most of the rest of the month working up. Manchester covered a minelaying operation in the Denmark Strait on 29 May–1 June before returning to Scapa on 4 June. Two days later, King George VI visited the ship during his visit to Scapa. The cruiser spent most of the next two weeks exercising with the other ships of the Home Fleet. On 19 June, Vice-Admiral Stuart Bonham Carter, commander of the 18th CS, hoisted his flag aboard Manchester. On 30 June–2 July, the ship ferried supplies and reinforcements to Spitzbergen Island in the Arctic Ocean. Immediately thereafter, she helped to provide distant cover for Convoy PQ 17 for the next two days. Upon her return to Scapa, she became a private ship when Bonham Carter struck his flag.[27]

Operation Pedestal

Main article: Operation Pedestal

Operation Pedestal, 11 August: A general view of the convoy under air attack showing the intense anti-aircraft barrage put up by the escorts. The battleship Rodney is on the left and Manchester is on the right.

Manchester was transferred to the 10th CS in preparation for Operation Pedestal, another convoy to resupply the besieged island of Malta. She departed Greenock on 4 August, part of the escort for the aircraft carrier Furious. They joined the main body of the convoy on the 7th off the coast of Portugal. The cruiser refuelled at Gibraltar and rejoined Force X, the convoy's close escort, on 10 August. Later that day, Eagle was sunk by a German submarine, the first casualty of many suffered by the convoy. By the night of 13/14 August, Force X was passing through the mine-free channel close off the Tunisian coast. At 00:40 the convoy was attacked by a pair of German S-boats, but they were driven off, with one boat damaged by British fire. About 20 minutes later Manchester was attacked near Kelibia by a pair of Italian MS boats (MTBs), MS 16 and MS 22, which each fired one torpedo, one of which struck the cruiser in the aft engine room, despite her efforts to evade the torpedoes, and jamming her rudder hard to starboard. The hit killed one officer and nine ratings and knocked out electrical power to the aft end of the ship. She slowed to a stop as both starboard propeller shafts were damaged and flooding of the aft engine room disabled both inner shafts. Only the port outer shaft was operable, but its turbine had temporarily lost steam due to the explosion.[28]

The flooding quickly caused Manchester to take on an 11-degree list and both the main radio room and the four-inch magazine to fill with water. At about 01:40 Drew ordered "Emergency Stations" which was a standing order when not already at action stations that required all crewmen not required to operate or supply the anti-aircraft guns to proceed to their abandon ship positions. Transferring oil from the starboard fuel tanks to port and jettisoning the starboard torpedoes reduced the list to about 4.5 degrees by 02:45. Drew felt that the ship's tactical situation was dire due to the threat of other motor torpedo boats as the ship's working armament was limited to the four-inch guns and the anti-aircraft weapons. He also felt it imperative that she had to reach deep water by the island of Zembra by dawn (05:30) which he estimated would take about three hours of steaming. The initial damage reports included a two- to three-hour estimate of restoring steam power as the extent of the damage had not yet been fully assessed, although that was repaired much more quickly than the initial estimate. Focused on the tactical situation, Drew was unaware that steam had been restored to the port outer turbine, the rudder unjammed and electrical power had been restored to the steering gear at about 02:02 before he decided to abandon ship 45 minutes later. Earlier, the destroyer Pathfinder had stopped to render assistance at 01:54 and Drew had transferred 172 wounded and superfluous crewmen before she had to depart to rejoin the convoy.[29]

About 02:30 Drew inquired about the necessary preparations for scuttling by her own crew with explosive charges during a conversation with his chief engineer. About 15 minutes later he addressed the crew informing them of his decision to scuttle the cruiser and to prepare to abandon ship. The order to scuttle was given at 02:50 and it was impossible to rescind when the chief engineer informed him that power had been restored to one turbine and the steering gear five minutes later. Manchester finally sank at 06:47. Drew ordered his crew to abandon ship at 03:45; one man drowned as he attempted to swim ashore, but the rest of his men survived. Most made it ashore, but an estimated 60 to 90 men were rescued by the destroyers Somali and Eskimo when they were dispatched at 07:13 to render assistance to the cruiser after Pathfinder met up the rest of the 10th CS. Two other men were rescued by an Italian MTB, but they were ultimately turned over to the French and joined the rest of the crew in the Laghouat prison camp.[30]

Aftermath

The Admiralty convened a Board of Enquiry on 16 September to establish the facts of the cruiser's loss using testimony provided by available witnesses. Rear-Admiral Bernard Rawlings, Assistant Chief of the Naval Staff (Foreign), and the First Sea Lord, Admiral Dudley Pound reviewed the board's findings and believed that Drew's actions showed a lack of determination to fight his ship. Pound further believed that this disqualified Drew from ever again commanding a ship unless further inquiry proved otherwise. First Lord of the Admiralty A. V. Alexander concurred with Pound's comments on 9 October.[31]

The interned crew was released after French North Africa joined Free France and all had arrived back in Britain by 25 November. Drew was ordered to write a report on the loss of his ship five days later by the Admiralty and forwarded his report on 7 December. A week later the Admiralty ordered that a court martial be convened for the loss of Manchester under article 92 of the Naval Discipline Act 1866 (29 & 30 Vict. c. 109) and it began on 2 March 1943.[32]

Drew's written evidence focused on the tactical situation in which he found himself: adrift in a narrow passage between the coast of Tunisia and an off-shore minefield, with the turret ammunition hoists disabled and little four-inch ammunition available and a high expectation of further attacks by MTBs and aircraft if still near the coast by dawn. He believed that any such successful attack would have a high chance of causing Manchester to run aground and fall into enemy hands. The initial damage control report given to him after the torpedo hit estimated three hours to get steam power restored which allowed him only a narrow window to get clear of the coast. His evidence made little mention of "Emergency Stations" and his reasoning behind evacuating unwounded crewmen aboard Pathfinder before ascertaining the full extent of the damage.[33]

After the modern Royal Navy's longest-ever court martial, the court determined that Manchester's damage was remarkably similar to that suffered on 23 July 1941 whilst under his command; that the cruiser was capable of steaming at 10–13 knots (19–24 km/h; 12–15 mph) on her port outer propeller shaft, that her main and secondary armament was largely intact, and that the initial list of 10–11 degrees had been considerably reduced via counter-flooding, jettisoning her torpedoes, and transfers of fuel oil. Drew was "dismissed his ship", severely reprimanded, and was prohibited from further command at sea; four other officers and a petty officer were also punished.[34]

A diving expedition visited the wreck at a depth of about 80 m (260 ft) in 2002 and footage taken by the divers was used in a TV documentary entitled Running the Gauntlet produced by Crispin Sadler. They discovered that the ship was largely intact, lying on her starboard side. Two of the ship's survivors accompanied the expedition and reminisced about their experiences.[35] Another diving expedition to view Manchester was undertaken in 2009.[36]

In November the cruiser was tasked to escort a convoy through the Mediterranean and participated in the Battle of Cape Spartivento. Manchester was refitting during most of early 1941, but began patrolling the southern reaches of the Arctic Ocean in May. The cruiser was detached to escort a convoy to Malta in July and she was badly damaged by an aerial torpedo en route. Repairs were not completed until April 1942 and the ship spent the next several months working up and escorting convoys.

Manchester participated in Operation Pedestal, another Malta convoy, in mid-1942; she was torpedoed by two Italian motor torpedo boats and subsequently scuttled by her crew. Casualties were limited to 10 men killed by the torpedo and 1 who drowned as the crew abandoned ship.[Note 1] Most of the crew were interned by the Vichy French when they drifted ashore. After their return in November, the ship's leadership was court martialled; the captain and four other officers were convicted for prematurely scuttling their ship.

Design and description

The Town-class light cruisers were designed as counters to the Japanese Mogami-class cruisers built during the early 1930s and the last batch of three ships was enlarged to accommodate more fire-control equipment and thicker armour.[2] The Gloucester group of ships were a little larger than the earlier ships of the class and received additional armour.[3] They displaced 9,400 long tons (9,551 t) at standard load and 11,650 long tons (11,837 t) at deep load. The cruisers had an overall length of 591 feet 6 inches (180.3 m), a beam of 62 feet 4 inches (19 m) and a draught of 20 feet 7 inches (6.3 m).[4] They were powered by four Parsons geared steam turbine sets, each driving one shaft using steam provided by four Admiralty 3-drum boilers. The turbines developed a total of 82,500 shaft horsepower (61,500 kW) and were designed to give a maximum speed of 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph).[5] During her sea trials on 28 March – 7 April 1938, Manchester achieved an average speed of 32.6 knots (60.4 km/h; 37.5 mph) from 84,461 shp (62,983 kW).[6] The ships carried enough fuel oil to give them a range of 6,000 nautical miles (11,000 km; 6,900 mi) at 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph). The ship's complement was 800–815 officers and ratings.[5]

The Town-class ships mounted twelve BL six-inch (152 mm) Mk XXIII guns in four triple-gun turrets, one superfiring pair each fore and aft of the superstructure. The turrets were designated 'A', 'B', 'X' and 'Y' from front to rear. Their secondary armament consisted of eight QF four-inch (102 mm) Mk XVI dual-purpose guns in twin mounts. Their light anti-aircraft armament consisted of a pair of quadruple mounts for the two-pounder (40-millimetre (1.6 in)) ("pom-pom") anti-aircraft (AA) guns and two quadruple mounts for 0.5-inch (12.7 mm) Vickers AA machine guns. The ships carried two above-water, triple mounts for 21-inch (533 mm) torpedoes.[7] The Towns lacked a full-length waterline armour belt, although the sides of the Gloucester group's boiler and engine rooms and the sides of the magazines were protected by 4.5 inches (114 mm) of armour.[7] The top of the magazines and the machinery spaces were protected by 1.25–2 inches (32–51 mm) of armour. The armour plates on the main-gun turrets had a thickness of 2–4 inches.[3]

The cruisers were designed to handle three Supermarine Walrus amphibious reconnaissance aircraft, one on the fixed D1H catapult and the others in the two hangars abreast the forward funnel, but only two were ever carried in service. A pair of 15,000-pound (6,800 kg) cranes were fitted to handle the aircraft and the ships' boats.[8]

Modifications

When Manchester returned home in November 1939, she was refitted with degaussing equipment and probably had her aft high-angle director-control tower (DCT) fitted. During a brief refit in November 1940, the ship was probably equipped with a Type 286 search radar. During a longer refit in January–March 1941, Manchester's hull was reinforced and her Vickers machine guns were exchanged for an ex-Army 40-millimeter Bofors AA gun atop 'B' turret and five 20-millimetre (0.8 in) Oerlikon AA guns. A Type 284 gunnery radar was installed on the roof of the main armament DCT atop the bridge during this refit. Additional splinter plating to protect the secondary armament and torpedo tubes was probably added at this time, as was an ASDIC sonar system.[9]

Two additional ex-Army Bofors guns reinforced the ship's anti-aircraft suite before she participated in Operation Substance in June 1941. Manchester was torpedoed during this convoy escort mission and while she was being repaired in the United States and Britain, she received three more Oerlikon guns for a total of eight weapons, six of which were positioned in the superstructure, one on the roof of 'X' turret and one on the quarterdeck. Two more ex-Army Bofors guns were added amidships before the ship participated in Operation Pedestal in August 1942. When the repairs were completed in April 1942, her radar suite consisted of a Type 279 early-warning radar, the Type 284 system for her main armament, two Type 285 gunnery radars for the four-inch guns, a Type 273 surface-search radar to replace the Type 286 and probably a pair of Type 282 gunnery radars for the "pom-pom" directors.[10]

Construction and career

Manchester, the first ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy,[11] was ordered on 23 October 1935 from Hawthorn Leslie and Company. The ship was laid down at their Hebburn shipyard on 28 March 1936 and was launched on 12 April 1937 by the wife of Joseph Toole, the Lord Mayor of Manchester. She was commissioned on 4 August 1938 and departed for her first duty assignment with the 4th Cruiser Squadron in the East Indies on 24 September.[12]

After arriving in the British Colony of Aden, Yemen, on 12 October, Manchester was met by the heavy cruiser Norfolk, the station flagship, and the two ships proceeded to Bombay, British India, and then to Trincomalee, British Ceylon by the end of the month where they spent the next month working up. They spent the next month making port visits on the western coast of British India before returning to Ceylon for a maintenance period in Colombo's dockyard. Ports along the Bay of Bengal were visited in February–March 1939, before the two cruisers arrived in Singapore in the British Straits Settlements on 13 March. They conducted exercises with the aircraft carrier Eagle, the heavy cruiser Kent and the submarine depot ship Medway off the eastern coast of Malaya for the next several weeks.[13]

Visiting Port Blair in the Andaman Islands en route on 28 March, Manchester arrived at Trincomalee to prepare for a refit in Colombo. Rising tensions in Europe caused the refit to be delayed for a week and her refit was completed in early June. She began a tour of Indian Ocean ports on 6 June, supporting an aeronautical survey in Diego Garcia three days later with fuel and supplies before arriving in the British Protectorate of Zanzibar on 20 June. The ship began moving up the African coast until she rendezvoused with her sister ship Gloucester, the new station flagship, at Kilindini Harbour in British Kenya on 14 July. The sisters sailed to Aden when they met the sloops Egret and Fleetwood later that month to practice convoy escort tactics in light of the potential threat posed by Italian colonies on the Red Sea.[14]

Early war service

Manchester had just returned from a patrol in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden when Britain declared war on Nazi Germany on 3 September 1939. Together with Gloucester, she sailed for Colombo after refuelling. On 25 September, the ship rendezvoused with the sloop Rochester to help escort an Indian troop convoy through the Red Sea. Manchester escorted an Anglo-French convoy there before rendezvousing with the ocean liner RMS Empress of Australia in the Gulf of Suez to escort her to Colombo. The cruiser was ordered home on 10 November and arrived at Malta eight days later, where Vice-Admiral Geoffrey Layton hoisted his flag as commander of the 18th Cruiser Squadron (CS). The ship arrived in HM Dockyard, Portsmouth on the 25th and was docked to have storm damage and some other defects repaired.[15]

Her refit was completed on 22 December and she joined the Home Fleet at Scapa Flow two days later. Later that month, Manchester was attached to the Northern Patrol, where she was tasked to enforce the blockade of Germany, searching for German blockade runners and contraband material. On 21 February 1940 the ship helped to capture the 4,709-gross register ton (GRT) German merchantman Wahehe.[16] She remained on this duty until early April, although the cruiser was in Scapa Flow when it was attacked by German aircraft on 16 March. Manchester's gunners were unprepared for the attack and her shells were ineffectual.[17]

Norwegian campaign

Main article: Norwegian campaign

The 18th CS was relieved of its attachment to the Northern Patrol and was assigned to escort convoys to and from Norway. On 7 April Manchester, her half-sister Southampton, the anti-aircraft cruiser Calcutta and four destroyers were escorting the 43 ships of Convoy ON-25 bound for Norway. After the Royal Air Force (RAF) reported German ships in the North Sea, the convoy was ordered to turn back and the two light cruisers were to rendezvous with the Home Fleet in the Norwegian Sea. Their orders were later modified to patrol the southern part of the sea. Late on the 8th, the Admiralty ordered the ships to rendezvous with the Home Fleet lest they be caught between the two groups of German ships believed to be at sea; this was accomplished early on the morning of 9 April.[18]

Reinforced by their sisters Sheffield and Glasgow and seven destroyers of the 4th Destroyer Flotilla, the 18th CS was ordered to attack the Königsberg-class cruiser believed to be in Bergen, Norway, later that morning. That afternoon the RAF reported two cruisers in Bergen and the Admiralty cancelled the operation. The Luftwaffe had been tracking the squadron as it approached Bergen and bombers from KG 26 and KG 30 began attacking shortly afterwards. They sank the destroyer Gurkha and near misses damaged Southampton and Glasgow. That night Manchester, Southampton and the 6th Destroyer Flotilla patrolled off Fedjeosen to observe German forces in Bergen and prevent any resupply. The only incident that night was when Manchester spotted a submarine crossing between the two cruisers on the surface; the ship attempted to ram, but only managed a glancing blow. The next morning, the ships were recalled and the cruisers arrived in Scapa Flow that evening to refuel and replenish ammunition.[19]

On 12 April, Captain Herbert Packer assumed command and the ship departed Scapa to rendezvous with the escort for Convoy NP-1 which was loaded with two infantry brigades bound for Narvik, Norway. Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided to take advantage of the unopposed occupation of Namsos on the 14th and ordered that the 146th Infantry Brigade should arrive offshore at dusk on the 15th to reinforce the initial landing force. Layton chose to escort the troopships Empress of Australia and MS Chrobry with Manchester, her half-sister HMS Birmingham (C19), the anti-aircraft cruiser Cairo and three destroyers. The threat of air attack and poor port facilities at Namsos caused the Admiralty to change the destination, but the troops and most of their equipment completed unloading on the 19th. That day the Admiralty ordered most of the ships off Norway home to prepare for further operations so the cruiser headed for Rosyth, Scotland.[20]

Later that day, Manchester was ordered back to the Namsos area to escort Convoy FP-1 back to Britain. On 22 April she returned to Rosyth to begin loading about half of the 15th Infantry Brigade, together with Birmingham and the heavy cruiser York, to be ferried to Åndalsnes and Molde. Manchester disembarked her passengers at the latter town on the 25th and then joined Birmingham to cover three destroyers laying mines near Trondheim. The sisters returned to Scapa Flow on 28 April to refuel. Three days later they arrived at Åndalsnes to evacuate the remaining troops still ashore. Manchester was slightly damaged by splinters from near misses made by the Luftwaffe that were otherwise ineffectual.[21]

On 10 May Manchester and Sheffield were ordered to sea to protect the crippled destroyer Kelly which was being towed home after having been torpedoed by an E-boat. The cruisers engaged Luftwaffe aircraft when they unsuccessfully attacked the next day and then were ordered to return to Rosyth in light of the submarine threat where she began a brief refit. On 26 May, the 18th CS, consisting of Manchester, Birmingham and Sheffield, was transferred to the Humber for anti-invasion duties. They returned to Rosyth on 10 June after the vulnerabilities of Immingham were realised. Layton was relieved by Vice-Admiral Frederick Edward-Collins on 15 June and the ships returned to Immingham on 1 July. Edward-Collins transferred his flag to Birmingham on 4 July after which Manchester sailed to Portsmouth to begin a brief refit. She arrived back in Scapa Flow on 22 August and Edward-Collins immediately returned his flag to the ship. Her stay there was brief as the squadron immediately sailed for Rosyth to resume anti-invasion duties. The squadron returned to Immingham on 3 September as fears of invasion rose. Edward-Collins was relieved by Vice-Admiral Lancelot Holland on 12 November.[22]

On 15 November the ship departed Scapa Flow to rendezvous with a convoy that conveying RAF personnel and equipment to Alexandria, Egypt. After their arrival in Gibraltar on 21 November, Manchester and Southampton loaded roughly 1,400 men and many tons of supplies and departed on the 25th, escorted by Force H. They were to be met by ships of the Mediterranean Fleet south of Sardinia, Italy, the whole affair codenamed Operation Collar. The Italians spotted the convoy and attempted to intercept it on 27 November in the Battle of Cape Spartivento. The British concentrated their cruisers, even though the efficiency of Manchester and Southampton was reduced by their passengers, and engaged their Italian counterparts at long range with little effect. The Italians attempted to disengage, but the British pursued until they risked leaving the convoy unprotected. The subsequent aerial attacks by the Regia Aeronautica (Royal Italian Airforce) failed to damage any British ships. During the battle, Manchester fired 912 shells from her main guns without making a single hit. But she was hit by the Italian battleship Vittorio Veneto causing splinter damage.[23] The ship arrived at Alexandria without further incident on 30 November. She passed through the Mediterranean at high speed without being spotted and arrived at Scapa Flow on 13 December. Holland transferred his flag to her half-sister Edinburgh on 8 January 1941. The cruiser began a lengthy refit at Jarrow on 11 January that lasted until 17 April.[24]

1941

Manchester rejoined the 18th CS at Scapa Flow the following day and spent the rest of the month working up. On 18 May the cruiser and Birmingham were ordered to patrol the Iceland-Faroe Islands gap, but they played no part in the search for the Bismarck as they were repositioned north of Iceland in case the German ships attempted to return to Germany through the Denmark Strait after the battlecruiser Hood was sunk on 24 May. The ships returned to Scapa Flow on 3 June and Packer was relieved by Captain Harold Drew. Manchester sailed on 9 June to Hvalfjord, Iceland, to patrol the Denmark Strait for the rest of the month, returning to Scapa on 3 July.[25]

The ship joined the escort force for Convoy WS-9C bound for Gibraltar on 12 July and arrived there eight days later where she loaded troops and supplies from the convoy to be conveyed to Malta in Operation Substance. The convoy came together on 23 July and the Italians determined that it was bound for Malta. The ships of the Regia Marina (Royal Italian Navy) were not prepared to attack so that was left to the bombers of the Regia Aeronautica. During the first attack that morning Manchester was hit by an Italian aerial torpedo that struck abreast 'X' turret. It blew a 60-foot-long (18.3 m) hole in the hull, disabled both portside propeller shafts, and allowed heavy flooding that caused a 12.5-degree list. The estimated 2,000 long tons (2,032 t) of water also caused the ship to trim down at the stern by 7 feet 6 inches (2.3 m) and filled the aft engine room which meant that only a single propeller shaft was operable. The detonation killed 3 officers and 23 ratings from Manchester's crew and 5 officers and 7 other ranks from the embarked troops. The list was corrected less than three hours after the attack and the cruiser was ordered to return to Gibraltar, escorted by a destroyer. The two ships were unsuccessfully attacked by more Italian bombers later that day and reached their destination on the 26th.[26]

Temporary repairs took until 15 September when the ship then sailed for the Philadelphia Navy Yard in the United States for permanent repairs. This was finished on 27 February 1942, after which she returned to Portsmouth, where final work was completed by the end of April. On her return to service she rejoined the Home Fleet at Scapa Flow on 4 May, spending most of the rest of the month working up. Manchester covered a minelaying operation in the Denmark Strait on 29 May–1 June before returning to Scapa on 4 June. Two days later, King George VI visited the ship during his visit to Scapa. The cruiser spent most of the next two weeks exercising with the other ships of the Home Fleet. On 19 June, Vice-Admiral Stuart Bonham Carter, commander of the 18th CS, hoisted his flag aboard Manchester. On 30 June–2 July, the ship ferried supplies and reinforcements to Spitzbergen Island in the Arctic Ocean. Immediately thereafter, she helped to provide distant cover for Convoy PQ 17 for the next two days. Upon her return to Scapa, she became a private ship when Bonham Carter struck his flag.[27]

Operation Pedestal

Main article: Operation Pedestal

Operation Pedestal, 11 August: A general view of the convoy under air attack showing the intense anti-aircraft barrage put up by the escorts. The battleship Rodney is on the left and Manchester is on the right.

Manchester was transferred to the 10th CS in preparation for Operation Pedestal, another convoy to resupply the besieged island of Malta. She departed Greenock on 4 August, part of the escort for the aircraft carrier Furious. They joined the main body of the convoy on the 7th off the coast of Portugal. The cruiser refuelled at Gibraltar and rejoined Force X, the convoy's close escort, on 10 August. Later that day, Eagle was sunk by a German submarine, the first casualty of many suffered by the convoy. By the night of 13/14 August, Force X was passing through the mine-free channel close off the Tunisian coast. At 00:40 the convoy was attacked by a pair of German S-boats, but they were driven off, with one boat damaged by British fire. About 20 minutes later Manchester was attacked near Kelibia by a pair of Italian MS boats (MTBs), MS 16 and MS 22, which each fired one torpedo, one of which struck the cruiser in the aft engine room, despite her efforts to evade the torpedoes, and jamming her rudder hard to starboard. The hit killed one officer and nine ratings and knocked out electrical power to the aft end of the ship. She slowed to a stop as both starboard propeller shafts were damaged and flooding of the aft engine room disabled both inner shafts. Only the port outer shaft was operable, but its turbine had temporarily lost steam due to the explosion.[28]

The flooding quickly caused Manchester to take on an 11-degree list and both the main radio room and the four-inch magazine to fill with water. At about 01:40 Drew ordered "Emergency Stations" which was a standing order when not already at action stations that required all crewmen not required to operate or supply the anti-aircraft guns to proceed to their abandon ship positions. Transferring oil from the starboard fuel tanks to port and jettisoning the starboard torpedoes reduced the list to about 4.5 degrees by 02:45. Drew felt that the ship's tactical situation was dire due to the threat of other motor torpedo boats as the ship's working armament was limited to the four-inch guns and the anti-aircraft weapons. He also felt it imperative that she had to reach deep water by the island of Zembra by dawn (05:30) which he estimated would take about three hours of steaming. The initial damage reports included a two- to three-hour estimate of restoring steam power as the extent of the damage had not yet been fully assessed, although that was repaired much more quickly than the initial estimate. Focused on the tactical situation, Drew was unaware that steam had been restored to the port outer turbine, the rudder unjammed and electrical power had been restored to the steering gear at about 02:02 before he decided to abandon ship 45 minutes later. Earlier, the destroyer Pathfinder had stopped to render assistance at 01:54 and Drew had transferred 172 wounded and superfluous crewmen before she had to depart to rejoin the convoy.[29]

About 02:30 Drew inquired about the necessary preparations for scuttling by her own crew with explosive charges during a conversation with his chief engineer. About 15 minutes later he addressed the crew informing them of his decision to scuttle the cruiser and to prepare to abandon ship. The order to scuttle was given at 02:50 and it was impossible to rescind when the chief engineer informed him that power had been restored to one turbine and the steering gear five minutes later. Manchester finally sank at 06:47. Drew ordered his crew to abandon ship at 03:45; one man drowned as he attempted to swim ashore, but the rest of his men survived. Most made it ashore, but an estimated 60 to 90 men were rescued by the destroyers Somali and Eskimo when they were dispatched at 07:13 to render assistance to the cruiser after Pathfinder met up the rest of the 10th CS. Two other men were rescued by an Italian MTB, but they were ultimately turned over to the French and joined the rest of the crew in the Laghouat prison camp.[30]

Aftermath

The Admiralty convened a Board of Enquiry on 16 September to establish the facts of the cruiser's loss using testimony provided by available witnesses. Rear-Admiral Bernard Rawlings, Assistant Chief of the Naval Staff (Foreign), and the First Sea Lord, Admiral Dudley Pound reviewed the board's findings and believed that Drew's actions showed a lack of determination to fight his ship. Pound further believed that this disqualified Drew from ever again commanding a ship unless further inquiry proved otherwise. First Lord of the Admiralty A. V. Alexander concurred with Pound's comments on 9 October.[31]

The interned crew was released after French North Africa joined Free France and all had arrived back in Britain by 25 November. Drew was ordered to write a report on the loss of his ship five days later by the Admiralty and forwarded his report on 7 December. A week later the Admiralty ordered that a court martial be convened for the loss of Manchester under article 92 of the Naval Discipline Act 1866 (29 & 30 Vict. c. 109) and it began on 2 March 1943.[32]

Drew's written evidence focused on the tactical situation in which he found himself: adrift in a narrow passage between the coast of Tunisia and an off-shore minefield, with the turret ammunition hoists disabled and little four-inch ammunition available and a high expectation of further attacks by MTBs and aircraft if still near the coast by dawn. He believed that any such successful attack would have a high chance of causing Manchester to run aground and fall into enemy hands. The initial damage control report given to him after the torpedo hit estimated three hours to get steam power restored which allowed him only a narrow window to get clear of the coast. His evidence made little mention of "Emergency Stations" and his reasoning behind evacuating unwounded crewmen aboard Pathfinder before ascertaining the full extent of the damage.[33]

After the modern Royal Navy's longest-ever court martial, the court determined that Manchester's damage was remarkably similar to that suffered on 23 July 1941 whilst under his command; that the cruiser was capable of steaming at 10–13 knots (19–24 km/h; 12–15 mph) on her port outer propeller shaft, that her main and secondary armament was largely intact, and that the initial list of 10–11 degrees had been considerably reduced via counter-flooding, jettisoning her torpedoes, and transfers of fuel oil. Drew was "dismissed his ship", severely reprimanded, and was prohibited from further command at sea; four other officers and a petty officer were also punished.[34]

A diving expedition visited the wreck at a depth of about 80 m (260 ft) in 2002 and footage taken by the divers was used in a TV documentary entitled Running the Gauntlet produced by Crispin Sadler. They discovered that the ship was largely intact, lying on her starboard side. Two of the ship's survivors accompanied the expedition and reminisced about their experiences.[35] Another diving expedition to view Manchester was undertaken in 2009.[36]

▲

⟩⟩

Mike Stoney

SimpleSailor

premecekcz

Len1

EdW

Wolle

Steves-s

Peejay

Ray

RodC

AlessandroSPQR

jumpugly

hermank

|

💬 Re: Pats HMS Manchester Video VE Day Celebrations 04 May 2025

4 months ago by 🇨🇦 Brightwork (

Commodore) Commodore)✧ 11 Views · 0 Likes

Flag

More Crap

▲

⟩⟩

No likes yet

This member will receive 1 point for every like received |

|

💬 Re: Pats HMS Manchester Video VE Day Celebrations 04 May 2025

7 months ago by 🇬🇧 Steves-s (

Chief Petty Officer 1st Class) Chief Petty Officer 1st Class)✧ 174 Views · 1 Like

Flag

I found the information about Manchester's history very interesting. Took me quite a while to read it all, but if I ever decided to build this type of ship, Manchester would be at the top of the list 👍👍 At the moment I will stick to WW2 models at 1/24th scale which are a bit less fiddly, at 36inches. Mine are a MTB and a HDML which I sail at the York Model Boat Club.

▲

⟩⟩

hermank

|

📝 One For The Sun Dodgers Video VE Day Celebrations at SMBC 04 May 2025

7 months ago by 🇬🇧 SouthportPat ( Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)

Commodore)✧ 201 Views · 7 Likes

Flag

💬 Add Comment

One For The Sun Dodgers Video VE Day Celebrations at SMBC 04 May 2025

▲

⟩⟩

premecekcz

Wolle

Peejay

Ray

RodC

AlessandroSPQR

hermank